Xu Bing was 11 years old when the Cultural Revolution began in China. He grew up in a land hostile to the printed word. Countless books were burned and reading was discouraged, unless it was Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book. His parents were both employed at the University of Beijing, were later deemed “reactionaries”, and imprisoned. Surprisingly, young Xu Bing was saved by words. He had demonstrated exceptional skill in calligraphy and typography; instead of being imprisoned with his parents, he was put to work in a propoganda office copying characters on posters, signs, and leaflets.

During the revolution, Mao Zedong attempted to transform Chinese culture by altering the language. The language reforms had two objectives: To make the written language more accessible to common people, and to bring Chinese into relation with other languages. Xu Bing describes how difficult this was for him since he had already learned thousands of characters and acquired a deep respect for his native tongue. By dictate, he was required to abandon many characters he knew and to learn new ones.[1] Words were used as weapons during the revolution and it’s not difficult to surmise how Xu Bing’s mistrust of language developed during this time.

After the revolution came to an end in 1976, there was a resurgence of creativity in China. Western books and ideas flooded in. Xu Bing compares himself at this time to, “…a person who was starving who gorges on too much food…the result was confusion and discomfort.”[2] By 1985, the New Wave art movement liberated artistic expression and brought new opportunities for avant-garde art groups. Taking advantage of the new liberties afforded him as an artist, Xu Bing exhibited in the China/Avant Gard show in Beijing in 1988. Initially, his work was well received, but a few months later, the massacre at Teinanman Square resulted in renewed suppression by the government. Xu Bing’s work was singled out for criticism and “Book From the Sky” was denounced as nihilistic and obscene. At that time, Xu Bing considered it prudent to leave China and emigrated to the United States in 1990.

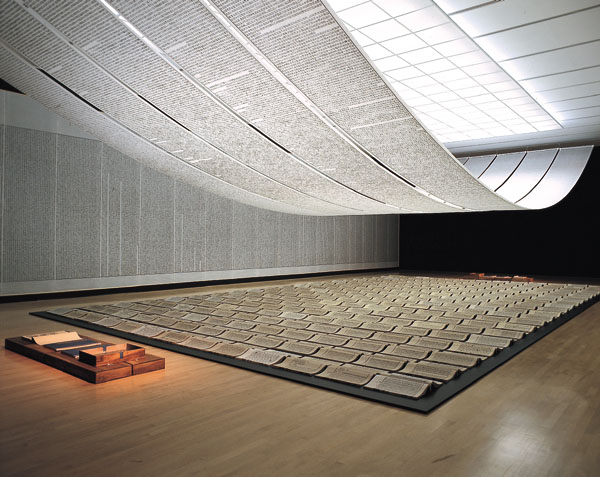

Now consider “Book From the Sky”. It’s a large installation composed of books, scrolls, and wall panels covered in a text that Xu Bing created himself. The viewer is surrounded by a text that can not be read. Chinese speakers become frustrated, finding themselves unable to decode the characters. Non-Chinese speakers will be fooled, thinking the text is Chinese.

What does it mean?

Words mean nothing.

“Book From the Sky” can be interpreted as an intentional strike at traditional views of language. In the introductory pages of his exhibition catalog (footnoted below) Xu Bing shares his opinion that our respect for language is a barrier that stifles new ideas. The title of this installation can also be translated “Book from the Heavens” and it does not take an extended leap of interpretation to see the subversive condemnation of sacred texts, as well. “Book from the Sky” asserts that heaven does not have anything meaningful to tell us, at least through intelligible texts. From his catalog we learn that Xu Bing is enthralled with the writings of Nietzsche and Wittgenstsein.[3] Nietzshe is best remembered for announcing, “God is dead”, but in his essay “Goodness and the Will to Power” he also wrote,”What is more harmful than any vice? Practical sympathy and pity for all the failures and all the weak: Christianity.”[4] Chew on the fact that one of Xu Bing’s favorite authors said Christianity is more harmful than any vice. Let that inform your understanding of his work. The philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein, claimed that language is nothing more than a social phenomenon.[5] The connection between Wittgenstein’s ideas and Xu Bing’s “Book From The Sky” is inescapable.

In the catalog of his work entitled, “Words Without Meaning, Meaning Without Words”, Xu Bing reveals ideas that seem problematic. Regarding “Book from the Sky” he says, “I want to remind people that culture restricts them.”[6] Surprisingly, a few pages later he claims that, “People and pigs are the same, except culture has changed people.”[7] According to Xu Bing, culture is the only thing separating us from uncultured swine. If that is true, it hardly seems desirable to cast aside our culture, however restrictive it may be.

Discrediting the relevance of language, he simultaneously draws us into language games. Let’s be honest. Without words we cannot talk about how meaningless his text is can we? He says words cannot describe his art and yet, here we are, using words to describe it.[8] Unfortunately, Xu Bing has been defeated by his own game. Listen to what he says concerning the myriad interpretations of his own work that he’s offered over the years: “I find it more and more difficult to answer questions that the work raises. By offering many different readings, I found myself in a new predicament. It’s as if I turned a simple situation into a more complicated one, falling into a bottomless pit of questions, a culture trap.”[9] It is possible that the trap he refers to is one of his own making?

Aesthetically, the installation is impressive. Line, light, and shadow combine in an expanse of contemplative installations. However, after researching the artist and his work, “Book from the Sky” raises serious questions.

How is the message in “Book From the Sky” any different from the propoganda of Chairman Mao? Mao deliberately debased the meaning in the Chinese language, and in doing so, damaged the culture. By suggesting that the West abandon its valuation of language, isn’t Xu Bing attempting to damage our culture, as well?

Most importantly, if we eliminate meaning in our language, what will we replace it with? Intuition? Oinking?

I’m not sure the West is ready for Xu Bing’s cultural liberation.

[1] “Words Without Meaning, Meaning Without Words: The Art of Xu Bing,” Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (University of Washington Press: Seattle and London, 2001), 33.

[4] Louis J. Pojman, Ethical Theory: Classical and Contemporary Readings (Belmont, CA: Thomson Learning, 2007), 162.

[5] R. Scott Smith, In Search of Moral Knowledge, Overcoming the Fact-Value Dichotomy (Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press), 182.

[9] Letter from Xu Bing to Michael Sullivan (September 1997): quoted in “The art of Xu Bing: Words without Meaning, Meaning without Words”, (Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 2001), 52.

Has anyone ever found or claimed to have found meaning in any of the characters from Book from the Sky?

I am doing a research paper for a college course and thought that this might be an important point specially if in reference to semiotics.

Hi Charles,

I don’t think anyone can find true semantic meaning in them, since they aren’t true symbols, but of course, many find personal meaning in them through subjective interpretation. All the best on your project!